|

Return To Main Page

Contact Us

Inside the Global Race to Turn Water Into Fuel

By Max

Bearak

Photographs by Giacomo

d’Orlando

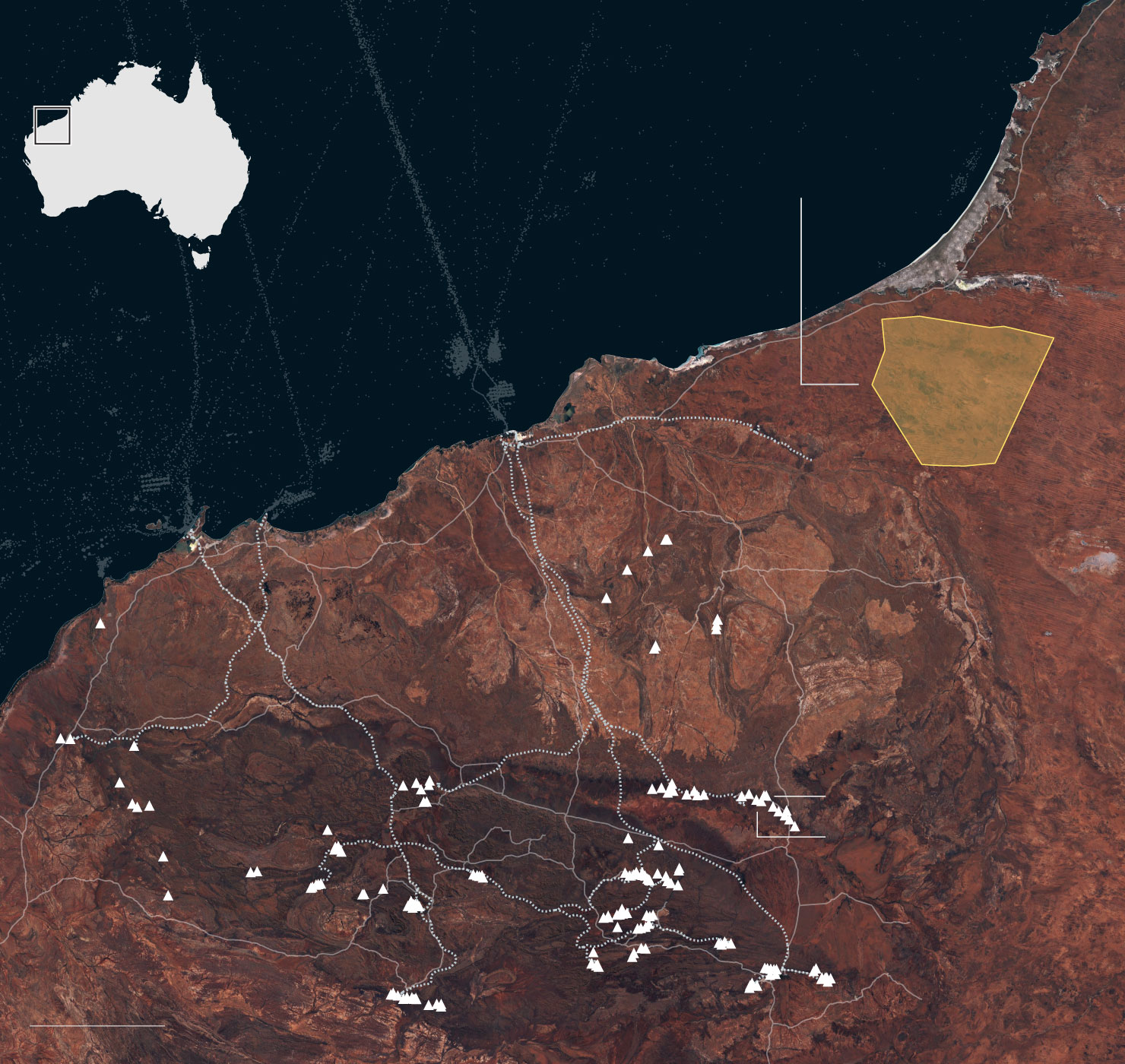

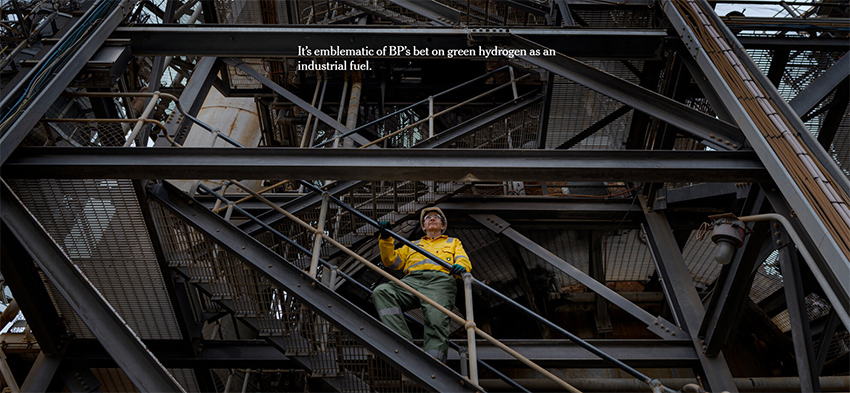

The Christmas Creek iron ore mine in Western Australia. Green

hydrogen producers

hope to find customers in the country’s huge mining industry, which

currently relies on fossil fuels.

Hundreds of billions of dollars are being invested in a high-tech gamble

to make hydrogen clean, cheap and widely available. In Australia’s

Outback, that starts with 10 million new solar panels.

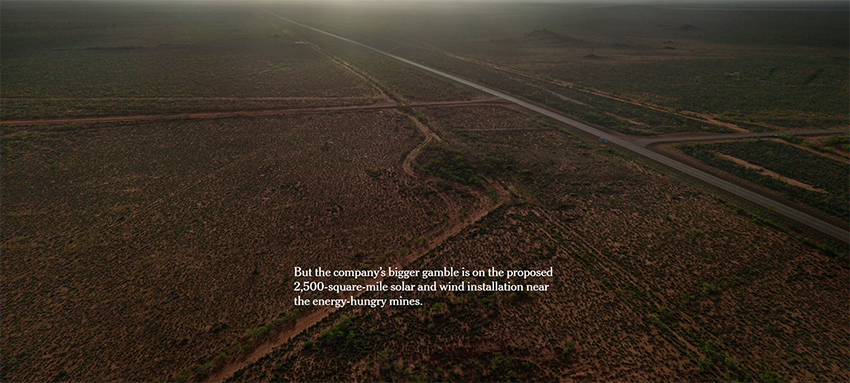

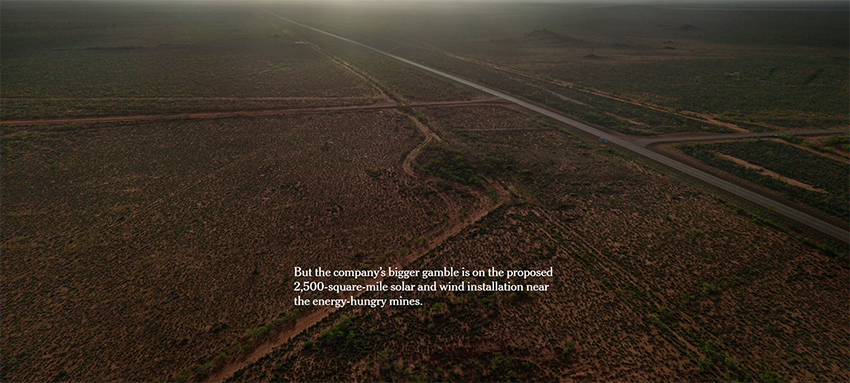

For eons this has been a quiet, unremarkable place. Thousands of square

miles of flat land covered in shrubs and red dirt. The sun is withering

and the wind blows hard.

It is exactly those features that qualify this remote parcel of the

Australian Outback for an imminent transformation. A consortium of energy

companies led by BP plans to cover an expanse of land eight times as large

as New York City with as many as 1,743 wind turbines, each nearly as tall

as the Empire State Building, along with 10 million or so solar panels and

more than a thousand miles of access roads to connect them all.

But none of the 26 gigawatts of energy the site expects to produce,

equivalent to a third of what Australia’s grid currently requires, will go

toward public use. Instead, it will be used to manufacture a novel kind of

industrial fuel: green hydrogen.

This patch of desert, more than 100 miles from the nearest town,

sits next to the biggest problem that green hydrogen could help solve:

vast iron ore mines that are full of machines powered by immense amounts

of dirty fossil fuels. Three of the world’s four biggest ore miners

operate dozens of mines here.

Proponents hope green hydrogen will clean up not only mining but

other industries by replacing fossil fuel use in steel making, shipping,

cement and elsewhere.

Green hydrogen is made by using renewable electricity to split

water’s molecules. (Currently most hydrogen is made by using natural gas,

a fossil fuel.) The hydrogen is then burned to power vehicles or do other

work. Because burning hydrogen emits only water vapor, green hydrogen

avoids carbon dioxide emissions from beginning to end.

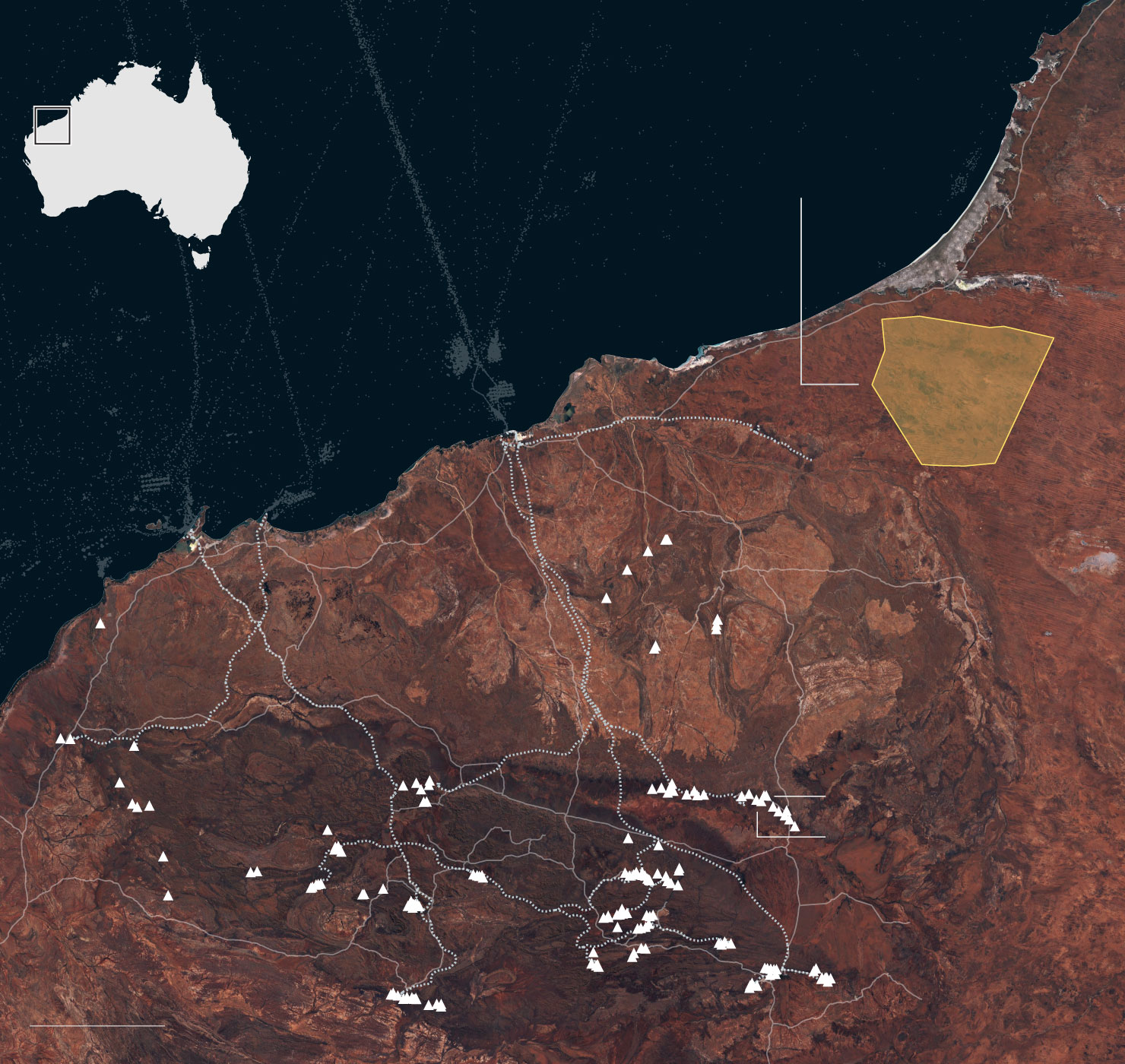

In the Pilbara region of Western Australia, and in dozens of spots around

the globe endowed with abundant wind and sun, investors see an opportunity

to generate renewable electricity so cheaply that using it to make green

hydrogen becomes economical. Even if only some of the projects come to

fruition, vast stretches of land would be duly transformed.

Note: Dots on cargo routes represent accumulated ship locations

Sources: BP, MariTrace, Australian Government

By Mira Rojanasakul/The New York Times

The project is one example of a global gamble, worth hundreds of billions

of dollars, being made by investors including some of the most polluting

industries in the world.

Last year, government subsidies sped up action in the European

Union, India, Australia, the United States and elsewhere. The Inflation

Reduction Act, the Biden administration’s landmark climate legislation,

aims to drive the domestic cost of green hydrogen down to a quarter of

what it is now in less than a decade through tax incentives and $9.5

billion in grants.

“We are about to jump from the starting blocks,” said Anja-Isabel

Dotzenrath, who once led Germany’s biggest renewable energy company and

now runs BP’s gas and low-carbon operations. “I think hydrogen will grow

even faster than wind and solar have.”

Not everyone sees it that way. Challenges loom on every level, from

molecular to geopolitical.

Some energy experts say green hydrogen’s business rationale is

mostly hype. Doubters accuse its champions of self-interest or even

self-delusion. Others see hydrogen as diverting crucial investment away

from surer emissions-reduction technologies, presenting a threat to

climate action.

Still, if the rosiest projections hold, green hydrogen in heavy

industry could reduce global carbon emissions by 5 percent, if not two or

three times that. In those scenarios, which are far from certain, hydrogen

plays a crucial role in limiting global warming.

Fatih Birol, the Turkish economist who leads the International

Energy Agency, said he seldom meets people who don’t find green hydrogen

alluring, with its elegant elementality. His organization forecasts that

green hydrogen will fulfill 10 percent of global energy needs by 2050.

He said the agency’s expectations were based on the fact that, if

the world wants to limit warming to 1.5 degrees, “so much green hydrogen

needs to be part of the game.”

A ‘Monstrous Challenge’

For green hydrogen to have a substantial climate impact, its most

essential use will be in steel making, a sprawling industry that produces

nearly a tenth of global carbon dioxide emissions, more than all the

world’s cars.

In climate lingo, steel emissions are “hard to abate.” Blast

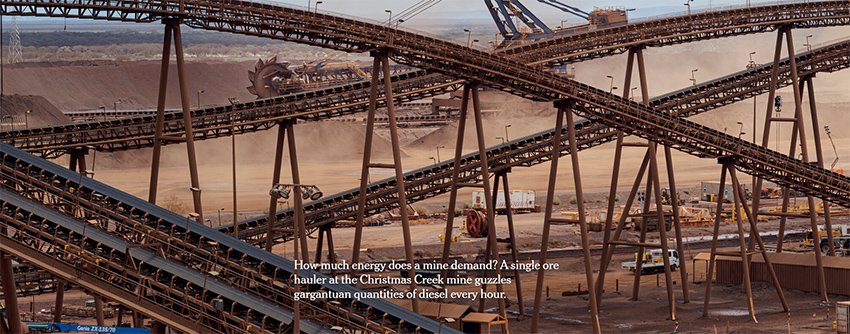

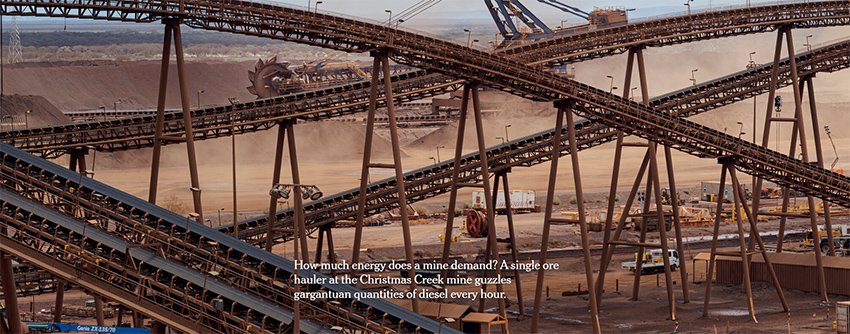

furnaces, freight trains, cargo ships and the gargantuan trucks used in

mining require heavy fuels like coal and oil. Even if they could be

electrified (and, as a practical matter, today many can’t be) they would

strain grids enormously.

Day and night, two-mile-long ore trains,

weighing more than 90 million pounds, depart Christmas Creek for

Port Hedland. From the port, an endless stream of cargo ships (once

again, burning heavy fuel) sail for East Asia, where ore becomes

steel in coal-burning mills.

Nearly 40 percent of the world’s iron ore comes from the Pilbara.

Wherever you are, when you look out at the world, some of what you

see is likely born of materials mined in and around Christmas Creek.

It wouldn’t be an overstatement to call the mine’s owner, Andrew

Forrest, the most bullish of hydrogen’s backers. When he said two

years ago that he was going to rapidly switch the mining operations

of his company, Fortescue Metals Group, to running fully on electric

batteries, green hydrogen and green ammonia, a fuel derived from

hydrogen, he was “met with mirth,” he said recently.

“Back then there was a distinct, visible horizon of disbelief that

the world could actually change,” said Mr. Forrest, who is also one

of the richest people in the world. He’s adamant that there’s a

market, even if others see folly.

Both Fortescue and BP envision themselves as

vying for the lead in green hydrogen and have announced plans to

invest hundreds of billions of dollars in projects across dozens of

countries beyond Australia, from Oman to Mauritania to Brazil and

the United States. Those would still account for only a smidgen of

the hundreds of millions of tons the I.E.A. and others say would be

needed to create a market in which green hydrogen was cheap enough

that steel and concrete makers were convinced to convert their

operations.

Even though both companies are hugely profitable, Australia’s

government has made hundreds of millions of dollars available to

them through subsidies and land allocations over the past two years,

mostly in Western Australia, which is six times the size of

California but has only 2 million people.

“Diesel has had 120 years to become plentiful and affordable,” said

Jim Herring, who oversees Fortescue’s green industry development.

“We want to scale hydrogen up in a tenth of that time. It’s a

monstrous challenge, honestly.”

The ‘Absolute Zero’ Problem

Iron ore on the way to Port Hedland.

To liquefy hydrogen for shipping, it must be

chilled to negative 252.87 degrees Celsius, just shy of absolute

zero, the theoretical temperature at which atoms are completely

still. Hydrogen is also very flammable, making storage difficult.

They’re just two of many obstacles.

Some doubts come from hydrogen’s advocates themselves. “The

economics of shipping aren’t looking good,” said Alan Finkel, the

architect of Australia’s hydrogen subsidies. “I was naïve, I think,

in the past to see export being the main demand driver,” he said in

a recent interview. Instead, “There’s a lot of sense in ‘use it

where you make it,’ and Australia is really ideally set up for

that,” he said.

Some are even more skeptical.

Saul Griffith, a prominent inventor in renewable energy who started

his career at an Australian steel mill, doesn’t see a big role for

green hydrogen. To replace fossil fuels, he said, “the electricity

you use to make it would have to be ridiculously cheap. And if you

have that, why use it to make hydrogen?”

He calls it “not a fuel that will save the world.” Better to spend

the money, he and others argue, on reducing renewable electricity

costs so that nearly everything can be electrified.

Mr. Forrest says skeptics simply lack

scientific knowledge. Fortescue, he said, will mix hydrogen with

carbon dioxide so it is similar enough in consistency to liquefied

natural gas that it can be transported in the same tankers.

“It’s is as simple as it sounds,” he said.

Mr. Forrest said he believed that, by decade’s end, he would save

his shareholders at least $1 billion a year by converting mining

operations to green hydrogen, and that his company would ultimately

produce hydrogen at dozens of sites worldwide. BP says it will be

exporting large quantities of green hydrogen and ammonia by then,

too.

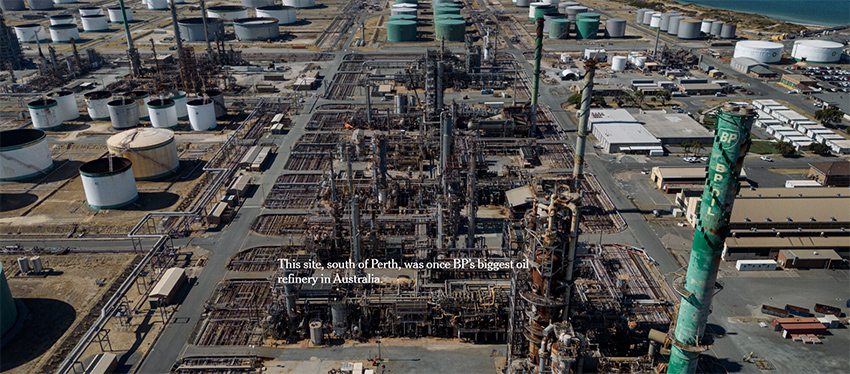

The interest taken in hydrogen by oil and gas companies concerns

some climate activists. While BP, for instance, has presented green

hydrogen as part of its pivot toward cleaner energy, the company

this year scaled back plans to phase down oil and gas production

over the coming decades amid record industrywide profits.

Energy companies already produce most of the world’s hydrogen fuel,

but make it from natural gas, which is, of course, a fossil fuel.

Some, including BP, stand to receive federal subsidies in the United

States because the company plans to capture the carbon and store it

rather than release it.

This is called “blue hydrogen,” and some critics consider it a

loophole in the Biden legislation that incentivizes fossil fuel

production.

Ms. Dotzenrath said opposing blue hydrogen amounted to letting the

perfect be the enemy of the good. “That’s absolutely nonsense,” she

said. “It’s ultimately all about the carbon intensity.”

But in Australia, at least, BP’s green hydrogen investments are

pushing ahead.

One of the impediments to huge green hydrogen

projects is the short supply of electrolyzers, the machines that use

electricity to split water molecules apart, isolating the hydrogen.

One issue is that China, which produces most of the world’s solar

panels, wind turbines and renewable energy tech, hasn’t embraced

electrolyzer production. Analysts said there was a shrewd calculus

to that: China is heavily invested in coal, and much of that is tied

to steel and cement production.

“It’s still a question: Will China go all in on hydrogen?” said

Marina Domingues, a clean technology analyst at Rystad Energy.

Despite the challenges, dozens of countries are betting on green

hydrogen. Last year, Spain, Portugal and France agreed to build an

undersea hydrogen pipeline by 2030 that would eventually supply the

rest of Europe. Japan, Taiwan and Singapore, which import nearly all

their energy, have also said hydrogen will be key to becoming carbon

neutral economies.

And Fortescue, for its part, is going into the business of making

electrolyzers. This month in Australia it is opening its first

factory, the world’s biggest.

The ‘Champagne’ of Energy

A solar farm that generates electricity for the Christmas Creek

mine.

For

Fortescue, the math is simple. Every year, each of its mines in the

Pilbara expands outward at least a couple miles. While the company

is developing 15-ton batteries to replace the diesel engines on some

of its ore haulers, the mine at Christmas Creek, for instance, is

already too sprawling for total reliance on batteries: New,

battery-powered haulers just won’t have the range for the mines’

farthest reaches.

Fortescue expects 70 percent of its fleet to be running on batteries

a decade from now — some powered by a mobile, 40-ton charger mounted

on a vehicle resembling a military tank. But the rest would run on

hydrogen or ammonia, replacing the billion-odd liters of diesel

Fortescue uses annually.

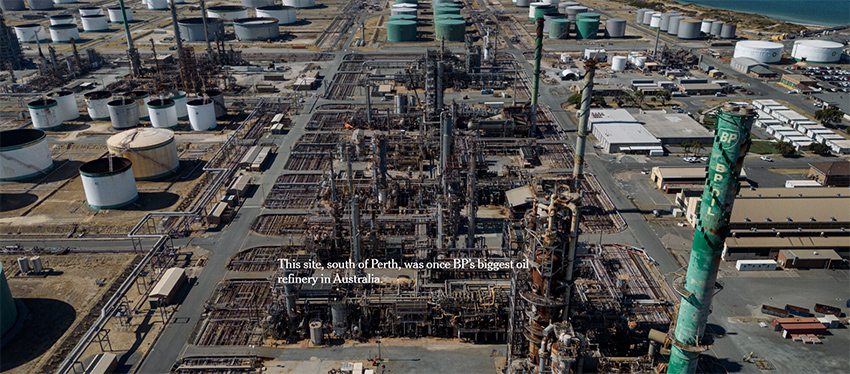

BP is taking a more measured approach. Many of its global projects

aim to produce blue hydrogen, which is cheaper, for now. Its green

hydrogen projects in Australia, including the repurposed refinery

near Perth, will come online in stages over a decade or longer.

Nevertheless BP, too, sees an inevitable shift toward green hydrogen

driven by increasingly stringent regulations in the United States,

European Union, Japan and South Korea.

In an “accelerated scenario” that envisions more ambitious

emissions-reduction targets set by the nations of the world, BP

predicts that, by 2050, green and blue hydrogen will be the

predominant fuels in steel production in those countries and will

also account for between 10 and 30 percent of fuel in aviation and

between 30 and 55 percent in shipping.

“Hydrogen,” Ms. Dotzenrath said, “is the champagne of the energy

transition.”

Green Play Ammonia™, Yielder® NFuel Energy.

Spokane, Washington. 99212

www.exactrix.com

509 995 1879 cell, Pacific.

Nathan1@greenplayammonia.com

exactrix@exactrix.com

|