|

Carbon

Compensation to $100 Billion. June 2, 2021

As net-zero commitments from companies ramp up, so does interest in

carbon offsets. It’s often the cheapest way to claim credit for

eliminating a ton of carbon dioxide, typically through a small fee to

protect forests or fund renewable energy. The company buying the

offset gets to erase emissions from its ledgers without spending far

larger sums to clean up its business.

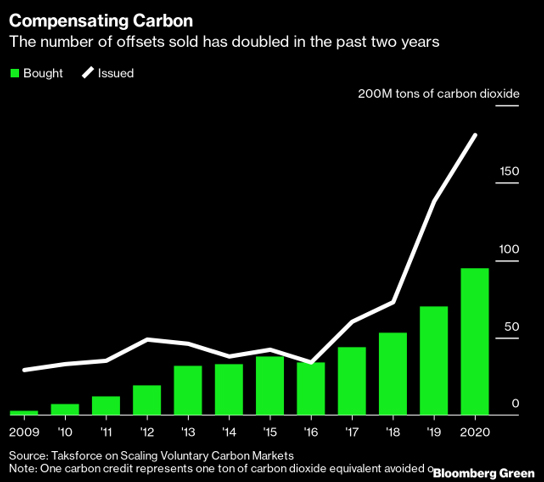

Such is the exuberance for carbon offsets that the consultancy

McKinsey & Co. estimates a voluntary trading market like the one being

organized by two financial heavyweights, Mark Carney and Standard

Chartered CEO Bill Winters, could be worth as much as $50 billion in

2030, up from just $300 million in 2018. Carney, the former governor

of the Bank of England, has put the figure as high as $100 billion by

the end of the decade.

In an interview last month, Winters said that private-sector demand

would be enormous. “People with money” know that offsets are “likely

to have tremendous support,” he said.

That’s one reason why late last year Winters and Carney launched the

Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets. The 400-plus group of

experts across industry, academia and finance are looking to produce

guidance within the next few months that will shape the global market.

But there are rifts within the closed-door taskforce, as my

Bloomberg Green

colleague Jess Shankleman and I reported today. In interviews with

more than a dozen members, we found impasses over what counts as a

credible offset and who can access the market. (Bloomberg

Philanthropies has pledged funding for the initiative.)

The bullish projections for carbon offsets underscore the importance

of a reformed and unified global market as a force bringing greater

transparency and higher standards than exists today. But there are

those within the ranks of experts who worry about the severe

limitations of carbon-offset projects and want the taskforce to

address the fundamental questions that have lingered for decades.

Time is running out. Winters and Carney hope to launch a pilot market

to trade carbon offsets later this year. The expectation is for the

new market to trade a benchmark contract that, with enough buyers and

sellers, can improve price discovery for offsets. That’s how the

currently opaque process by which companies purchase offsets can

mature into something more like a recognized commodity.

Brent crude is one such benchmark contract, accounting for about 60%

of all the world’s oil traded on any given day. That doesn’t mean that

60% of the world’s oil comes from the North Sea, the source of the oil

used to create the Brent benchmark, only that most barrels of oil are

close enough in quality to be measured against the Brent standard.

West African crude tends to trade at anything from a few cents less

than Brent to a $2 discount, depending on characteristics like sulfur

content and viscosity.

There’s a lesson in this for the commodification of carbon offsets—and

a thorny problem. For a contract to be a benchmark, it needs to be a

significant share of the total market. The vast majority of the

offsets sold today cost less than $5 for each ton of carbon dioxide

removed from the atmosphere. In many cases, the price per ton can be

as low as $2. Winters has said that low-cost offsets are unlikely to

meet the high bar that the taskforce is looking to set. If the current

market is dominated by offsets that are too cheap, it could take years

before there’s enough high-quality offsets to support a benchmark

contract akin to Brent crude.

It’s likewise unclear if there will be as many buyers as needed for

enough liquidity in the market to achieve true price discovery. That’s

because groups like the widely followed Science-Based Targets

initiative, or SBTi, currently prohibit offsets for meeting short-term

corporate climate goals. SBTi has said it may allow the use of offsets

in the future for hard-to-cut emissions, such as those from air

travel, but only when there aren’t promising technological

alternatives. The issue of who can and can’t buy offsets, and for what

purpose, remains a subject of intense debate within the taskforce.

Perhaps the biggest unsolved issue is the concern that carbon offsets

won’t become as fungible a commodity as corn or copper. Trees that

store away carbon dioxide for five years before being burned in a

wildfire are providing a fundamentally different service than a ton of

the gas buried deep underground for thousands of years. Climate change

is a problem of cumulative amount of greenhouse gases in the

atmosphere, and many experts argue that the longer a ton of CO₂

can be stored away, the more valuable it should be. That might make it

hard to set a standardized price.

Even if the new market considered only offsets from trees, it might

prove vulnerable. Several

investigations

over the past year have shown that the trade in forestry offsets can

be easily gamed. “Those who have moved early to ask which offset

credits are real, are the people who learn the hardest that very of

them are real,” said Danny Cullenward, a lecturer at Stanford Law

School with an expertise in carbon removal who isn’t involved in the

taskforce. He said those involved in the market-process are at risk

of “putting the people who have stood up these programs historically

in charge of defining quality.”

The offset market, if it comes together, will be self-regulated.

That’s key to the approach put together by Carney and Winters, and

it’s even in the name: Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets.

Buyers and sellers are incentivized to trade numbers on ledgers, but

how can the rules incentivize verification? Will all the offsets

trading hands in the new market truly lower greenhouse-gas emissions?

As one taskforce participant we spoke to put it: Either the taskforce

recommends the creation of a global regulator, or it risks the same

failure that has met previous attempts.

— With assistance from Jess Shankleman and Alex Longley

Akshat Rathi writes the Net Zero newsletter, which examines the

world’s race to cut emissions through the lens of business, science,

and technology. You can

email him

with feedback.

Green Play Ammonia™, Yielder® NFuel Energy.

Spokane, Washington. 99212

www.exactrix.com

509 995 1879 cell, Pacific.

exactrix@exactrix.com

|