|

Return To Main Page

Contact Us

Scientists warn of ‘phosphogeddon’ as critical fertiliser

shortages loom

Mar 12, 2023

By Robin

McKie,

Science editor

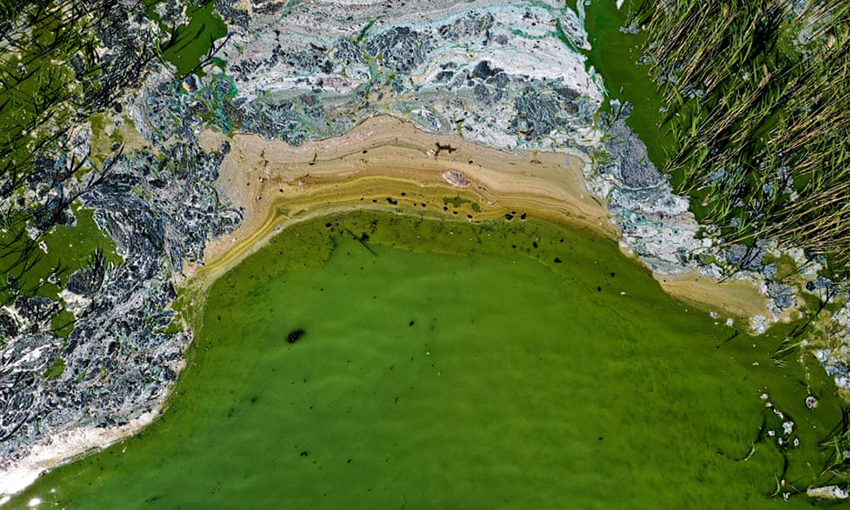

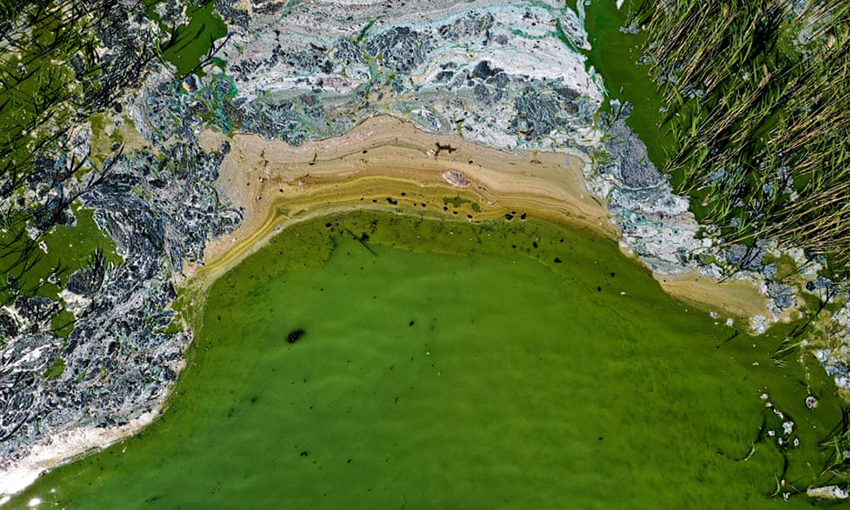

The overuse of phosphorus is creating algal blooms such as

the one in the Baltic Sea near Stockholm in Sweden. Photograph:

TT News Agency/Reuters

Excessive use of phosphorus is depleting reserves

vital to global food production, while also adding to the climate crisis

Our planet faces “phosphogeddon”, scientists have warned. They fear

our misuse of phosphorus could lead to deadly shortages of fertilisers

that would disrupt global food production.

At the same time, phosphate fertiliser washed from fields –

together with sewage inputs into rivers, lakes and seas – is giving rise

to widespread algal blooms and creating aquatic dead zones that threaten

fish stocks.

In addition, overuse of the element is increasing releases of

methane across the planet, adding to global heating and the climate crisis

caused by carbon emissions, researchers have warned.

“We have reached a critical turning point,” said Prof Phil Haygarth

of Lancaster University. “We might be able to turn back but we have really

got to pull ourselves together and be an awful lot smarter in the way we

use phosphorus. If we don’t, we face a calamity that we have termed ‘phosphogeddon’.”

Phosphorus was discovered in 1669 by the German scientist Hennig

Brandt, who isolated it from urine, and it has since been shown to be

essential to life. Bones and teeth are largely made of the mineral calcium

phosphate – a compound derived from it – while the element also provides

DNA with its sugar phosphate backbone.

“To put it simply, there is no life on Earth without phosphorus,”

exlpained Prof Penny Johnes of Bristol University.

The element’s global importance lies in its use to help crop

growth. About 50m tonnes of phosphate fertiliser are sold around the world

every year, and these supplies play a crucial role in feeding the planet’s

8 billion inhabitants.

However, significant deposits of phosphorus are found in only a few

countries: Morocco and western Sahara have the largest amount, China the

second biggest deposit and Algeria the third. In contrast, reserves in the

US are down to 1% of previous levels, while Britain has always had to rely

on imports. “Traditional rock phosphate reserves are relatively rare and

have become depleted in line with their extraction for fertiliser

production,” added Johnes.

This growing strain on stocks has raised fears the world will reach

“peak phosphorus” in a few years. Supplies will then decline, leaving many

nations struggling to obtain enough to feed their people.

The prospect concerns many analysts, who worry that a few cartels

could soon control most of the world’s supplies and leave the west highly

vulnerable to soaring prices. The result would be the phosphate equivalent

of the oil crisis of the 1970s.

The predicament was once summed up by the science fiction writer

Isaac Asimov: “Life can multiply until all the phosphorus is gone and then

there is an inexorable halt which nothing can prevent.”

These dangers were also highlighted last week with the publication

in the US of The Devil’s Element: Phosphorus and a World Out of Balance,

by the environment writer Dan Egan. The book has yet to be published in

the UK but it mirrors concerns recently raised by British scientists.

They say we have become profligate in the use of phosphates we put

on our fields. Fertiliser washed from them – and discharges of

phosphorus-rich effluent – have triggered large-scale contamination of

water and created harmful algal blooms. Some of the world’s biggest bodies

of freshwater are now afflicted, including Russia’s Lake Baikal, Lake

Victoria in Africa and North America’s Lake Erie. Blooms at Erie have led

to poisoning of local drinking water in recent years.

“Just as they do on land, phosphates help aquatic plants to grow,”

said Haygarth, who is the co-author of Phosphorus: Past and Future. “And

that is now having calamitous consequences in rivers, lakes and

seas.”Choked by blooms, many of these bodies of water have become dead

zones, where few creatures survive and which are expanding. One dead zone

now forms in the Gulf of Mexico every summer, for example.

Such crises also create other environmental problems. “Climate

change means we will get more algal blooms per unit of phosphate pollution

because of the warmer conditions,” said Prof Bryan Spears of the UK Centre

for Ecology & Hydrology in Midlothian.

“The problem is that when that algae dies, it can

decay to produce methane. So a rise in blooms will mean more methane will

be pumped into the atmosphere – and methane is 80 times more potent than

carbon dioxide at warming the atmosphere. It is a cause for real concern.”

Spears led a team, which included Haygarth and Johnes, that wrote a recent

report, Our Phosphorus Future, in which they outline the measures needed

to head off our impending crisis. These include improving ways to recycle

phosphorus and to ensure there is a global shift to healthy diets with low

phosphorus footprints.

The global spread of the element reveals how profoundly humanity is

now shaping the makeup of our planet, added Johnes. “In one case, we dig

up ancient carbon deposits of coal, oil and gas, burn them and so pump

billions of tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, triggering

climate change.

“With phosphorus, we are also mining mineral reserves but in this

case we are turning them into fertiliser which is washed into rivers and

seas where they are triggering algal blooms. In both cases these grand

translocations are causing planetary havoc.”

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you move on, I was

hoping you would consider taking the step of supporting the Guardian’s

journalism.

From Elon Musk to Rupert Murdoch, a small number of billionaire

owners have a powerful hold on so much of the information that reaches the

public about what’s happening in the world. The Guardian is different. We

have no billionaire owner or shareholders to consider. Our journalism is

produced to serve the public interest – not profit motives.

And we avoid the trap that befalls much US media – the tendency,

born of a desire to please all sides, to engage in false equivalence in

the name of neutrality. While fairness guides everything we do, we know

there is a right and a wrong position in the fight against racism and for

reproductive justice. When we report on issues like the climate crisis,

we’re not afraid to name who is responsible. And as a global news

organization, we’re able to provide a fresh, outsider perspective on US

politics – one so often missing from the insular American media bubble.

Around the world, readers can access the Guardian’s paywall-free

journalism because of our unique reader-supported model. That’s because of

people like you. Our readers keep us independent, beholden to no outside

influence and accessible to everyone – whether they can afford to pay for

news, or not.

Green Play Ammonia™, Yielder® NFuel Energy.

Spokane, Washington. 99212

www.exactrix.com

509 995 1879 cell, Pacific.

Nathan1@greenplayammonia.com

exactrix@exactrix.com

|